Amitabh Shukla

Lucknow has changed and keeps changing

like all other cities but the basic character, linguistic uniqueness and

cuisine along with its famous tehjeeb remains

an integral part of the Uttar Pradesh Capital

Travelling

by train invariably has a charm and attraction associated with it, the larger

picture being a laidback journey and the beginning of an unwinding exercise. I

always look forward to a leisurely train journey in which you can slip into

slippers and shorts, pull out the snacks or home cooked food from the upper

layer of the backpack, put your phone in the charging sockets, drink the

occasional khaki water which often passes off as tea, put one foot over the

other and relax looking outside the sealed window.

This

train journey was necessitated due to a cousin’s wedding in Lucknow, the city

of the Nawabas and where the “pehle aap” (you first) culture is the

legend of folklore, instead of “me first” as is believed to be the norm

everywhere. I got a hint of this later while de-boarding the train at Lucknow

station where my co-passenger, insisted that I get down first and I insisted he

gets down first. He prevailed and I got down.

Anyway,

boarding a night train from Chandigarh to the Capital of Uttar Pradesh was

eventless and so was easing into the AC compartment and catching a sleep,

hoping to be in Lucknow by the time I woke up in the morning. That was not to

be. The train was late by 3 hours as I checked the mobile app for updates early

in the morning. “You are spending an extra three hours in the comfort of AC in

the same price of the ticket,” a fellow passenger, who appeared to be a marketing

professional as his phone conversations suggested, told me, when I informed him

about the status of the train. “Was I amused?” No, for sure.

Just

before Lucknow, the Capital of erstwhile royalty of Awadh, the train made an

unscheduled stoppage at Kakori, a small station which is a part of the legend

of revolutionaries who fought for the freedom of the country. As I came near

the coach door, I could see a red signal at some distance and got down at the

station, hoping to run and catch the train again when the signal turned green. It

was here at this station that one evening on August 9, 1925, the

revolutionaries led by Ramprasad Bismil stopped a local train and looted the

money which the guard was carrying to finance their struggle against

colonialism in the country. The plaque

which has been put up at the station says that revolutionaries boarded the

Saharanpur passenger from this station. The moment, the train started from

Kakori, Bismil pulled the chain which stopped it a little ahead of the station.

Chandra Shekhar Azad, Asfaqullah Khan, Rajendra Nath were in this train,

besides others. One person was inadvertently killed in the incident. “They took

the government money in their custody and challenged the British empire by this

act,” the plaque at the station said.

History

books have it that in the Kakori trial, which assumed nationwide importance and

caught the attention of the entire country, Ram Prasad Bismil, Thakur Roshan

Singh, Rajendra Nath Lahiri and Ashfaqullah Khan were sentenced to death and later

hanged. Some of them were sent to Cellular Jail in Port Blair in punishment then

called Kala Paani. Chandra Shekhar

Azad, who was never caught, shot himself dead in Alfred Park Allahabad, now

known after his name when he was cornered by the British a few years later. “Kakori

was a landmark in Indian freedom struggle as it catapulted national

consciousness and gave a definite direction to the movement for overthrow of

the British regime,” historians have a consensus on this.

After

a stoppage of half an hour or so, the signal turned green and the train started

moving again and I caught it after surveying the station, people and the disinterested

railway officials, who were hardly aware of the event. The Kakori memorial, in

memory of the revolutionaries, has been built close to the station and you can

see it from the train window if it is moving at a slow pace.

Soon,

the train entered the outskirts of Lucknow and then the crowded station itself.

I could see a big crowd at the platform through the window. As co passengers

collected their luggage and moved towards the exit doors, I waited for a while

before exiting where I came face to face with the tehjeeb (cultural and behavioral norms) of the city where a

co-passenger, the marketing professional who had asked me about the train

timing earlier, asked me to get down first. We couldn’t get introduced to each

other but smiled as we headed for the exit.

This

was my second visit to the city, the first being almost a decade and a half

back and that too only for an evening. So practically, it was my first visit as

I had seen nothing then, except the airport, transfer to a hotel and then

catching a morning flight back to Delhi.

Courtesy

a friend placed in a high position in Uttar Pradesh government, a vehicle was

sent to fetch me from the station to the government guest house where my

lodging arrangements had been made. “I have been waiting for the last four

hours, train services are so unreliable these days,” said driver Sarfaraj

Ahmed, who had been sent to receive me at the station. “Yes,” I nodded in

agreement, as the government driver from the Rajya Sampati Vibhag (government property department) of Uttar

Pradesh helped me with the backpack. The number plate of the vehicle in Hindi

script too had the name of the department engrossed boldly in Hindi so that the

cops do not stop a government vehicle even if it violates traffic rules.

Strangely,

it was named VVIP guest house and was indeed located in an area close to the

place where who and who of UP resided—Governor, chief minister, former chief

ministers, present ministers and Judges. For the first time I realized the

limitations of the bureaucracy and the netas

as they had failed to name a guest house properly. They could have named it after

one of the greats from the state which has given most of the Prime Ministers to

the country. Curious about the name, I enquired about it from the reception and

was told that it was actually called Ati

Vishist Athithi Griha and nothing else and its English translation Board

too was put up proclaiming it to be a “VVIP Guest House”. Anyways, it was a two

room well maintained and comfortable suite with a drawing room, bed room and it

also had a small office table with chairs separately in a corner.

Getting

to the wedding venue of my cousin Aditya in the evening was easy as it was in a

five-star hotel and the driver knew the entire city like the back of his hand. Now,

there is a striking similarity in weddings all over north India, be it Punjab, Haryana,

Himachal, Delhi, UP, MP or Bihar. There are hardly any regional differences

when it comes to playing the DJ, hiring a band, lighting arrangements, dancing

to the same tunes time and again and then the food which is becoming common in

all weddings despite geographical differences.

Here

also, the baraat or the groom’s

wedding party came from their home in vehicles and stopped 50 meters from the

wedding venue, the lawns of the hotel. Heavily dressed men and women assembled,

some of them poured perfumes on themselves, saw one last time in the mirror

which they had brought in from their homes and then the moving DJ started

playing the typical wedding songs. And it was dance all the way for the 50

metres to the venue of the wedding. No one for sure had danced anywhere except

in weddings of relatives. But here, they were up to it—freestyle dancing, no

rhythm or synchronized movements but hands and feet were moving in all

directions.

Usual

video making exercise and still photo shoots, ritually going up the stage and

pose for the photo, waiters forcing snacks and drinks at you—all the rituals

you associate with an Indian wedding was there. You could simply sit there and

close your eyes. If you have been to one north Indian wedding, you need not go

to any other. It has become so standardized that it is the same everywhere,

right from clothes, food, dance, rituals and what not. Only the faces change,

nothing else. But I still remember the stuffed Tikki and the Chaat,

exceptionally well made, the only items I had for the wedding dinner, besides

some fruits.

I

always prefer morning walks in a new place to explore the area, feel its pulse

and vibration, talk to the people to understand and assimilate the accent and

their thought process and also to rejuvenate myself for the day. So, there I

was, at 6 am sharp, clad in sneakers T-shirt and track pant, I was on the

deserted street. I passed through the road in front of the massive Raj Bhawan

where the Governor lives and was in a park near the colonial building of the

General Post Office. The architecture of GPO, an imposing colonial structure in

White colour is indeed impressive. It was built in the 1920s and used for various

forms of entertainment by the British even as entry of Indians was banned here

in those days. Now, the residents of Lucknow use it for postal services. The

outer façade had been well maintained and prima facie suggested of a glorious

heritage. The trial of the famous Kakori conspiracy case, which I mentioned

earlier, took place here apparently due to security reasons. I took a round in

the park near it, had a look at the GPO Clock Tower located here and recreate

the past in my mind.

Then,

I moved towards the Christ Church, the gates of which were closed at this time

of the morning. Initially built in 1810 with additions later on, in the Gothic

style of architecture, the style used in most of the European churches, it has

a great history of its own and has braved many a storm in the last two

centuries of its existence. It houses so many things now—cemetery, educational

institution and also a Church and is witness to the evolution of the British

empire in Awadh, ruled by the Nawabs

before the colonial power came to the region and annexed it in 1856.

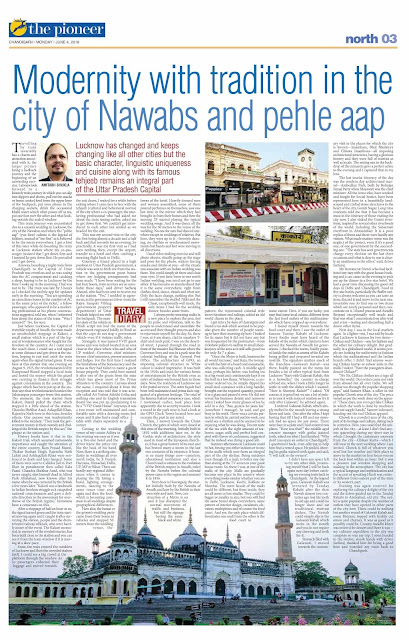

Next

door is Hazratganj, the market initially built by the Nawabs of Awadh and later

by the British in their own style and taste. Now, construction of a Metro is on

and it has disrupted the normal movement of traffic and business, but still the

signage having the same black and white pattern, the rejuvenated colonial style

street furniture and railings, added an old world charm to the place.

I

got into a by-lane of Hazratganj and found a tea stall which seemed to be

popular given the number of people wanting to have their morning sip here. I

looked for its name but it did not have any but was frequented by the

proletariat—from rickshaw pullers to sadhus to small shopkeepers of the area as

it still sells good tea for only Rs 7 a glass.

“Once

the Metro is built, business for all would increase,” said Raju, the teenager

with the hint of a beard and moustache, who was collecting cash. A middle aged

man, perhaps his father, was boiling tea in a big vessel and continuously kept

it on the boil in a low flame. Whenever, a customer ordered tea, he simply

dipped his small steel container with a long handle, brought out the required

quantity, poured it in a glass and passed it over. He did not reveal his

business details and turnover when I asked how many glasses of tea he sold in a

day. “Bas, guzara ho jaata hai”

(somehow I manage), he said, and got busy in his work. There was a certain

pattern in which he carried out his work, you could see a rhythm and he seemed

to be enjoying what he was doing. Decent taste of the tea with the right amount

of tea-leaves, sugar, milk and perfect boil coupled with flavor of cardamom, suggested

that he indeed was doing a good job.

Summer

afternoons in Lucknow could be hot, forcing you either indoors or in one of the

malls which now form an integral part of the city skyline. Being outdoors even

though it’s a mall, is better any day than staring at the TV screen in your

guest house room. So, there I was, at one of the malls of the city. Malls are

gradually become one place in the country where everything looks similar

whether you are in Delhi, Lucknow, Kochi, Kolkata or Mumbai. The outer facade of

the malls could be different, but from inside, they are all more or less

similar. They could be bigger or smaller in size, but you will find the same

brand shops everywhere, same pattern of interior design, escalators, elevators,

multiplexes and of course the food court. And yes, the only place which

differentiates one mall from the other is the food court to some extent. Here,

if you are lucky, you may find some local cuisine, different from the fast food

outlets of the multinationals which have cropped up everywhere.

I

found myself drawn towards the food court and there I saw the outlet of famous

Tunday Kababi of Lucknow. Every foodie must have heard of the kababs of the

outlet which claims to have served the Nawabs of Awadh for generations. I

checked the menu, boldly painted inside the outlet as aroma of the Kababs being

grilled and prepared invaded my nostrils. The signature mutton snack of the

franchise—Galawati Kabab—was there, boldly painted on the menu list besides a

lot of other typical food from Lucknow. “Start with Galawati Kabab, this is a

bestseller,” the counter in-charge advised me, when I took a little longer to

settle in with the dishes which I wanted. “How is Shammi Kabab?” I asked. “Of

course, it is good but we use a lot of pulses to mix it with minced mutton so

try it only after Galawati,” he advised again.

I

ordered Galawati Kabab, which simply melted in the mouth leaving a strong

flavor and taste. One after the other, I

kept having that till I had a fill and my stomach had no space for any more.

There were four in a plate and I had ordered two plates. “How was that?” the

middle aged counter manager with gutka stained teeth, asked me after I had

finished. “Why don’t you open an outlet in Chandigarh,” I questioned back, even

offering to help him find a rented space. He smiled, showing his gutka stained

teeth again and said, “I will talk to the owners”.

I

didn’t have any space left to try any other dish, promising myself that I will

be back again next day before catching my evening train back to Chandigarh. As the legend goes, Galawati Kabab was

invented by Tunday Kababi after the then Nawab almost two centuries ago lost

his teeth in old age and could no longer chew and eat traditional mutton

dishes. The Nawab could simply slip in the Galawati Kabab which melts in the

mouth and you do not require any chewing and teeth for it.

Stomach

filed with Galawati, I moved towards the customary visit to the places for

which the city is known—Imambara, Bhul Bhulaiyya and Chhota Imambara—all

imposing architectural structures, having a glorious history and they were full

of tourists as well as locals. The setting sun in the backdrop of the minarets

gave a perfect adieu to the evening and I captured that in my lens.

The

last tourist itinerary of the day was the modern day architectural

marvel—Ambedkar Park, built by Bahujan Samaj Party when Mayawati was the chief

minister. All the icons who, have worked and fought for Social Justice, have

been represented here in a beautifully landscaped and crafted stone structures

in the heart of the city, Gomti Nagar. Long time residents told me that it has

become a must in the itinerary of those visiting the city now. I also visited

the Gomti riverfront, inspired by several other riverfronts of the world,

including the Sabarmati riverfront in Ahmedabad. It is a poor replica of those

and there were hardly any visitors. What made matters worse was the neglect of

the project, even if it’s a good one, of one government by the succeeding one.

“The state has seen governments change every election on the last three

occasions and what is dear to one is clearly an anathema to the other,” said,

driver Sarfaraj.

My

bureaucrat friend, who had facilitated my stay with the guest house booking and

a car, came in the evening to pick me up for dinner in a five-star hotel. We

had a great time discussing the good old days in Delhi and Chandigarh. Food in

five-star hotels, particularly the Buffet variety is always welcome as you can

taste an item, discard it and move to the next one. Invariably you do find one

or two items which are nicely prepared and then concentrate on it. I found prawns

and Awadhi Biriyani exceptionally well made and that was what I concentrated on

after trial and error—tasting and discarding half a dozen other items.

Next

day, I was in the local markets again. In

a lighter vein, I was told by locals that Lucknow is famous for two

items—Chikan and Chicken—one for fashion and the other for culinary delight.

But gradually, in a globalised world, it seems people are looking for

uniformity in fashion which the multinational and the Indian brands offer. I didn’t

find anyone wearing Chikan kurtas or salwar suits in the malls I visited. “Have

the youngsters abandoned Chikan?”.

“No

Sir, Chikan clothes are a rage all over the world. Our orders come not only

from abroad but all over India. We sell online too through the popular shopping

apps,” said Sameer Khan, a seller in the popular Chowk area of the city. The

price varied as per the work done on the apparel. “These days, you even get

fake Chikan in which the work is done by machines and not supple hands,” Sameer

informed, handing out the real Chikan apparel.

Chowk

is a crowded area of the city, part of its heritage and culture, dating back to

centuries. Here, you could find the tahjeeb

of the city—at least I din’t find anyone quarreling during my short stay in

which I bought the customary souvenir from the city—Chikan Kurta—which I will

wear in the next wedding where I am invited. Chowk is full of whatever you need

but hot weather and little place to move in the market on foot forces you on

the back foot within an hour. But it was a pleasure just window shopping and

soaking in the atmosphere. The city has a typical language and sophistication

and the accent of speaking Hindi was entirely different from eastern part of

the state or its western part.

Evening

was again reserved for exploring the culinary delight of the city and the

driver guided me to the Tunday Kababi in Aminabad, old city. The outlet is

quite popular despite the number of outlets they have opened in other parts of

the city now. There could be nothing but another round of Galawati Kabab and

some Biriyani, topped with freshly cut onion and chutney. It was as good as it

possibly could be. Creamy Awadhi kheer was ordered for dessert and there it

was—my culinary expedition to the city was complete so was my trip. I soon

headed to the station, shook hands with driver Sarfaraj, thanked him for being

a good host and boarded my train back to Chandigarh. (June 4, 2018)